[Edited on 10-9-25 to include The Life of a Showgirl.]

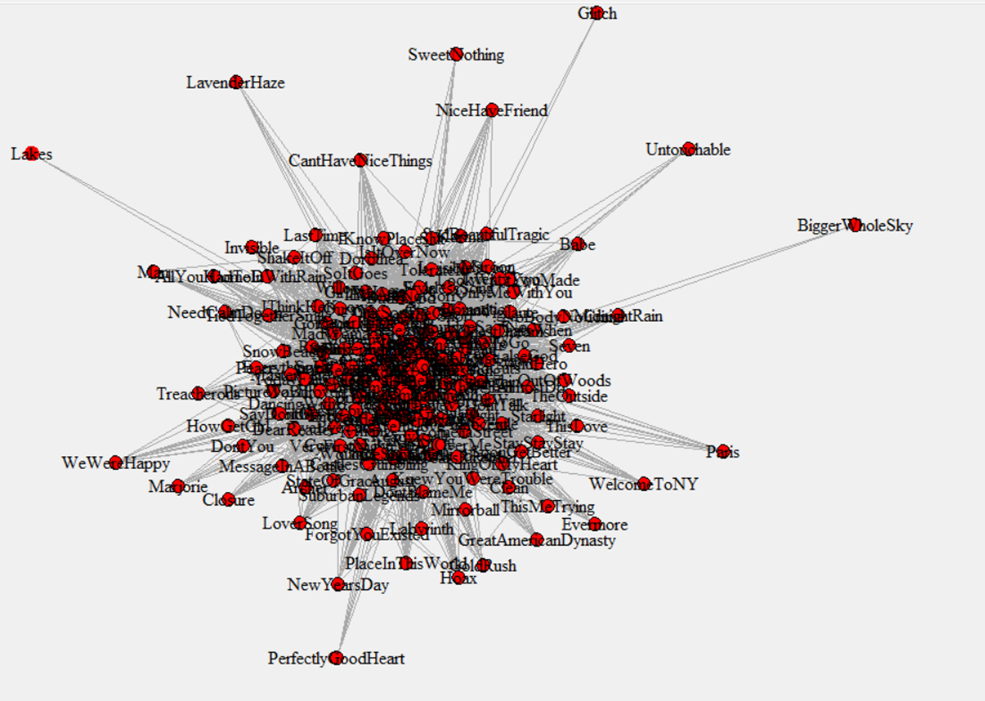

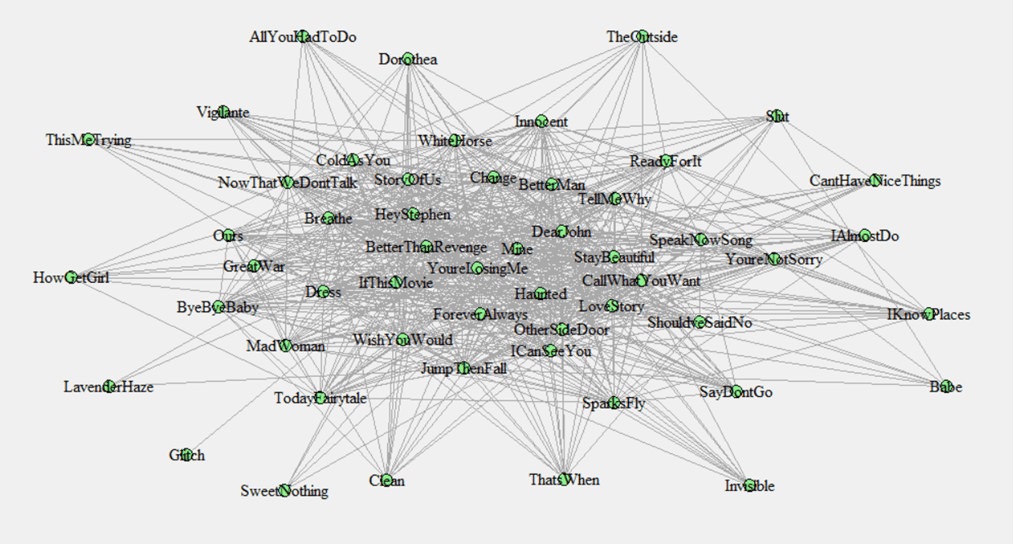

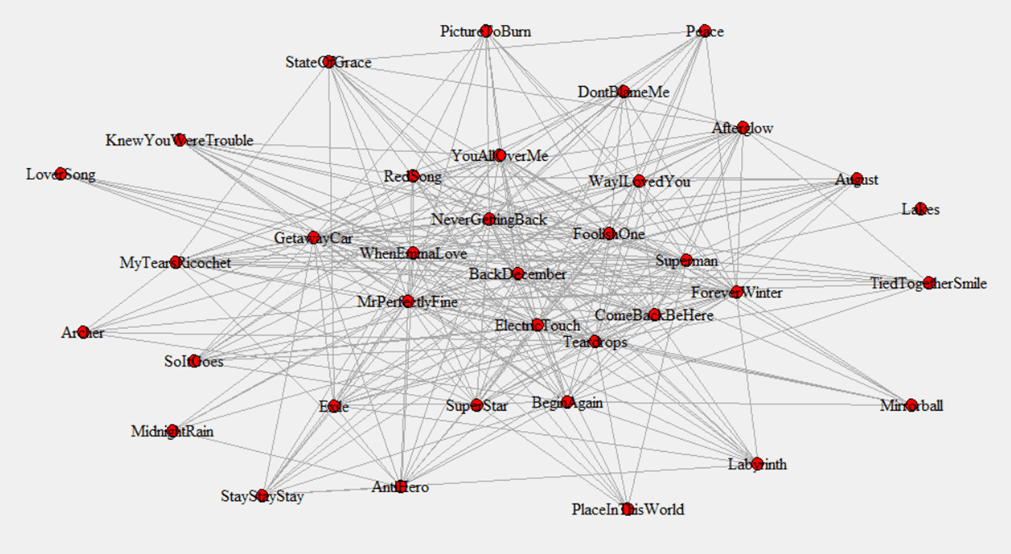

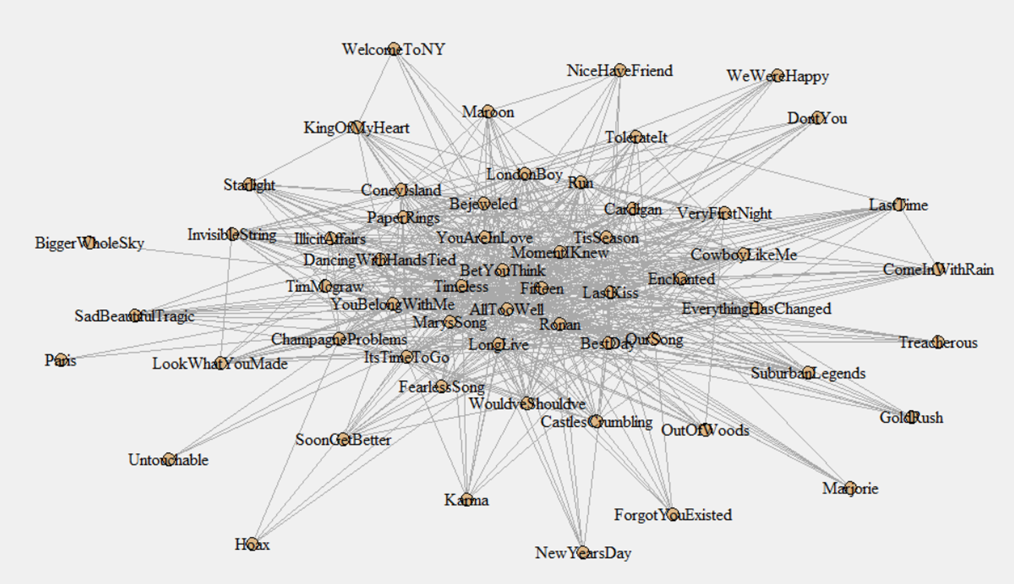

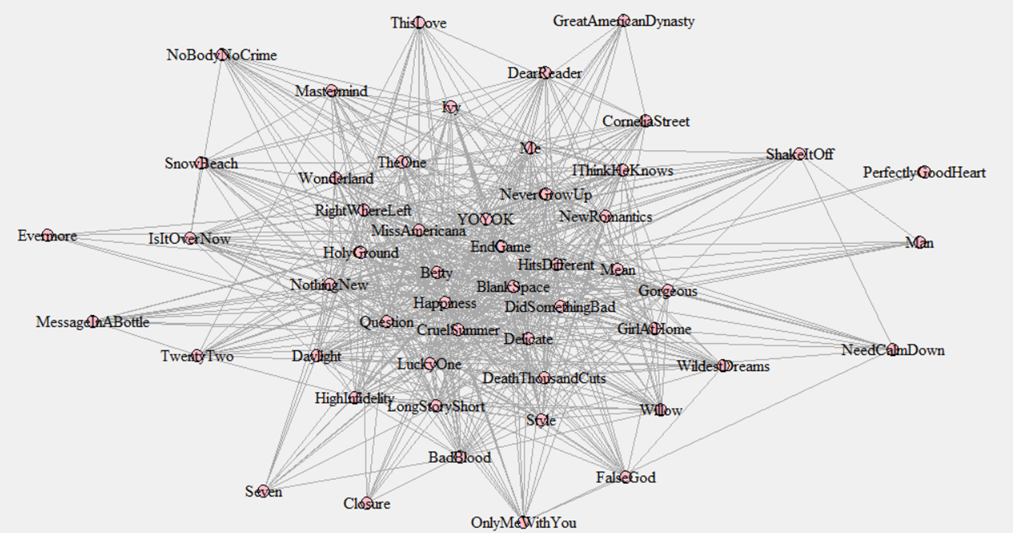

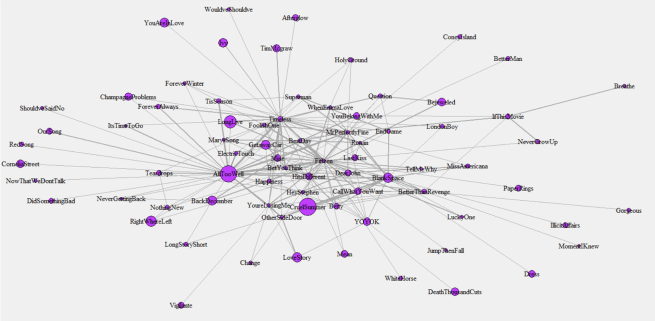

I published a peer-reviewed academic journal article that conducted a semantic network analysis of all of Taylor Swift’s songs on her debut album through Midnights. Essentially, the analysis created a “map” showing how these songs were related to each other, and in a previous post I described the four song types identified in this map. In order to be connected, songs needed to have at least 13 words in common (of course, 13!), with more words indicating a stronger connection. Here’s an example of what part of the map looks like:

From this map, we can calculate the “centrality” of the song. This refers to how well-connected the song is to other Taylor Swift songs; in other words, it tells us how central the song is in the “Taylorverse.” One of the main findings from the anlaysis was that songs with higher centrality are more popular (as measured by stream count, expert rankings, and social media conversation). So, although there are certainly exceptions, the songs at the center of the Taylorverse are more beloved than those at the periphery.

But, which are the songs that are most central? Well, here’s the complete list (as of October 9, 2025), going from most central to least central. It includes all songs on the main studio albums, and, unlike the published analysis, I’ve included The Tortured Poets Department and The Life of a Showgirl! In addition to listing the songs in descending order of centrality, I’ve also broken them into five groups based on their centrality.

Before we begin, it’s worth remembering that this isn’t a ranking of the best Taylor Swift songs, nor my personal opinion (you can find my complete ranking of her songs that list elsewhere). Rather, it is a list of which songs share the most word overlap with other songs. But, as you scan the list, I think you’ll see that the central songs do tend to be more popular (with exceptions), and those on the periphery less popular (again, with exceptions).

The Center of the Taylorverse

- Fifteen

- Timeless

- All Too Well

- But Daddy I Love Him

- Mr. Perfectly Fine

- Blank Space

- Hits Different

- I Bet You Think About Me

- Better Than Revenge

- Betty

- Mine

In addition to being the top ten eleven, all of these songs have centrality scores that exceed the traditional threshold for statistical significance (for fellow stats nerds, z > 1.96). Aside from the Speak Now Vault track “Timeless,” which wasn’t particularly well received, the others are fan favorites. Most are singles and/or Eras Tour songs; of course megahit “All Too Well” would end up here. And with oft-repeated Swiftian words like love, door[s], boys, girls, time, just, and dancing, “Fifteen” is a prime example of core Swiftian language and, as of this analysis, is at the very heart of the discography, semantically speaking.

Also in the Taylorverse’s Core

- You’re Losing Me

- Foolish One

- You’re On Your Own, Kid

- Dear John

- Ronan

- When Emma Falls in Love

- imgonnagetyouback

- Electric Touch

- The Life of a Showgirl

- If This Was a Movie

- Call it What You Want

- The Other Side of the Door

- End Game

- Teardrops on My Guitar

- Happiness

- Last Kiss

- So Long London

- loml

- The Moment I Knew

- Cruel Summer

- Superman

- Love Story

- The Best Day

- Long Live

- Florida!!!

- … Question?

- Forever & Always

- You Belong With Me

- Miss Americana & the Heartbreak Prince

- Mary’s Song

- I Hate it Here

These songs don’t quite break the top 10, but do exceed one standard deviation above the average for centrality. It makes sense that “You’re On Your Own, Kid,” which metaphorically narrates Swift’s career, would score toward the center. Other big hits in this group include “Dear John,” “Teardrops on My Guitar,” “Love Story,” and “Cruel Summer.”

Above Average Centrality

- Hey Stephen

- Never Grow Up

- The Story of Us

- We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together

- The Bolter

- Better Man

- Haunted

- I Did Something Bad

- Getaway Car

- Right Where You Left Me

- Back to December

- Forever Winter

- The Lucky One

- Tell Me Why

- Nothing New

- Holy Ground

- Peter

- Breathe

- Death by a Thousand Cuts

- You Are in Love

- White Horse

- Thank You Aimee

- Cancelled!

- Jump Then Fall

- So High School

- ‘Tis the Damn Season

- I Can See You

- Now That We Don’t Talk

- Bejeweled

- Sparks Fly

- Stay Beautiful

- I Wish You Would

- Delicate

- Mean

- Red

- Our Song

- Long Story Short

- Enchanted

- Begin Again

- Daylight

- … Ready For It?

- Tim McGraw

- The Way I Loved You

- Should’ve Said No

- Fresh Out the Slammer

- Eldest Daughter

- Change

- Opalite

- Wonderland

- SuperStar

- London Boy

- Style

- Paper Rings

- Innocent

- Illicit Affairs

- Dress

- Come Back, Be Here

- Gorgeous

- Speak Now

These songs have a centrality score between the mean and one standard deviation above it. You’ll recognize lots of Taylor classics here, including the debut single “Tim McGraw,” hits like “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together” and “Style,” and the song that anchored the Speak Now Eras Tour set, “Enchanted.”

Below Average Song Centrality

- Me!

- Guilty as Sin

- New Romantics

- Elizabeth Taylor

- High Infidelity

- You All Over Me

- Mad Woman

- Everything Has Changed

- Cardigan

- Bad Blood

- The 1

- Coney Island

- Would’ve, Could’ve, Should’ve

- It’s Time to Go

- Girl at Home

- Afterflow

- Bye Bye Baby

- Champagne Problems

- Honey

- The Great War

- Ivy

- Run

- Cold as You

- Dancing With Our Hands Tied

- Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?

- Cornelia Street

- Today was a Fairytale

- My Tears Ricochet

- Ours

- I Can Do It With a Broken Heart

- Chloe or Sam or Sophia or Marcus

- August

- You’re Not Sorry

- The Very First Night

- Exile

- Actually Romantic

- Fearless

- I Think He Knows

- Castles Crumbling

- My Boy Only Breaks His Favorite Toys

- Mastermind

- Clara Bow

- False God

- Willow

- Wildest Dreams

- So It Goes

- Vigilante Shit

- Tolerate It

- The Prophecy

- Invisible String

- I Almost Do

- Anti-Hero

- Snow on the Beach

- Wi$h Li$t

- The Black Dog

- Don’t Blame Me

- The Tortured Poets Department

- Say Don’t Go

- Dear Reader

- Picture to Burn

- Dorothea

- Starlight

- King of My Heart

- The Manuscript

- I Knew You Were Trouble.

- State of Grace

- Is it Over Now?

- Down Bad

- Stay Stay Stay

- Look What You Made Me Do

- Suburban Legends

- Peace

- Father Figure

- I’m Only Me When I’m With You

- Slut!

- Soon You’ll Get Better

- That’s When

- Tied Together with a Smile

- 22

- Out of the Woods

- Cassandra

- Clean

- The Fate of Ophelia

- Mirrorball

- Ruin the Friendship

- Maroon

- Karma

- No Body No Crime

- I Know Places

- Seven

- Labyrinth

- The Archer

- Shake It Off

- Sad Beautiful Tragic

- The Last Time

- Don’t You

- Message in a Bottle

- The Outside

- Come in With the Rain

- This Love

- I Forgot That You Existed

- The Alchemy

- How You Get the Girl

- You Need to Calm Down

- Lover

- This is Me Trying

With centrality scores from the mean down to one standard deviation below it, these songs have less than average word overlap with other songs. Although there are certainly some hits here (“I Can Do it With a Broken Heart”; “Champagne Problems”; “Out of the Woods”), many songs are deeper cuts on their respective albums.

The Edge of the Taylorverse

- Midnight Rain

- Hoax

- Place in This World

- Gold Rush

- Treacherous

- Invisible

- The Last Great American Dynasty

- How Did It End?

- Babe

- Closure

- This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

- All You Had to Do Was Stay

- Marjorie

- Evermore

- Wood

- Welcome to New York

- New Year’s Day

- The Man

- We Were Happy

- I Can Fix Him (No, Really I Can)

- Fortnight

- I Look in People’s Windows

- It’s Nice to Have a Friend

- A Perfectly Good Heart

- Paris

- Lavender Haze

- Sweet Nothing

- Untouchable

- Bigger Than the Whole Sky

- Glitch

- The Albatross

- The Lakes

- Robin

- Epiphany

Again, it’s worth remembering that having low song centrality doesn’t mean a song is bad. Here, at the semantic fringe of the Taylorverse, I find songs I personally enjoy, such as “Midnight Rain,” “Treacherous,” “Evermore,” and “The Lakes.” But, with the exception of “The Man” and “Fortnight,” this is generally a list of lesser-known songs. It makes sense that “Epiphany,” which concerns the experiences of Swift’s grandfather in World War II and doctors during COVID, would have the lowest centrality: its subject matter differs from any other song in the discography.

This isn’t a list I plan to update regularly, if ever, because updating the map takes some effort. [Edit: OK, I couldn’t resist when TLOAS came out.] Nevertheless, I hope it provides a different perspective on how we might consider, rank, and understand the amazing body of work that is the Taylorverse.