“Gray November, I’ve been down since July.” The opening lyric from the “Evermore” title track hits different now. In July, the surgeon removed the polyp that revealed the presence of stage 3 rectal cancer. And I spent the entire month of November in daily chemoradiation to treat it.

I’m 46. This all emerged after my first routine colonoscopy. If you are 45 or older, get one; if you are 40 or older, and you have any ability to have a colonoscopy done, I hope you will. It is a very good idea and not as onerous as people make it sound. I certainly wish I had. I’d go back in time and change that, but I can’t.

Since 2009, Taylor Swift’s music has been a constant companion in the journey of my life. And so it has been in the shadowy and uncertain journey of cancer.

During my screening MRIs, I asked the technicians to play Taylor Swift while I was in the tube. It was a practical decision as well as an emotional one. I know the length of many Swift songs, at least roughly, so when they told me the scan would take about 45 minutes, Taylor both entertained me and let me know how much time I had remaining.

Fast forward to October 27, the first day of radiation treatment. The nurses asked what music I wanted, and when I said Swift, one of the nurses lit up. “We don’t get many Swifties around here!” she said.

“Are you a Swiftie?” I asked. Indeed she was! Later, I learned that she rearranged her schedule so she could have me as a patient and listen to Taylor Swift with me during my treatment. By the end, Nurse Allison even knew how to seed the Pandora station so that it gravitated toward my favorites.

Then there’s the waiting for appointments, an inevitable part of any major medical issue. Early in the treatment cycle, I printed out the lyrics of some of Swift’s most semantically-central songs. I don’t want to steal my own thunder for what might become a future paper, but suffice it to say that, as I sat waiting for radiation therapy, a hospital robe my only clothing to speak of, I busied and distracted myself with a pen and paper, conducting rhetorical analysis of some of her most famous lyrics. I hate it here, so analyzing those lyrics became lunar valleys in my mind.

Now we are back to December, the season of Advent (and, for many Swifties, of the Evermore album). I have finished five weeks of chemoradiation, and later this month, I will begin a chemotherapy regimen that will last 3 months. The hope is that this will take care of the cancer, and that future scans and scopes will reveal no tumor. If so, life continues. If not—and there is a substantial chance the treatment will not be completely effective—I likely will need surgery to remove my rectum. That would be life-changing.

If the opening line of “Evermore” is uncanny, the bridge, that powerful duet between Justin Vernon and Taylor Swift, is an emotional gut-punch. I mean, so many of her bridges are, but this one has taken on deep subjective meaning for me. It’s likely not with meaning she intended, but that’s ok; such is art, whose meaning often is a joint creation between the artist and the audience.

Vernon:

Can’t not think of all the cost, and the things that will be lost.

Oh, can we just get a pause? To be certain we’ll be tall again.

Whether weather be the frost, or the violence of the dog days

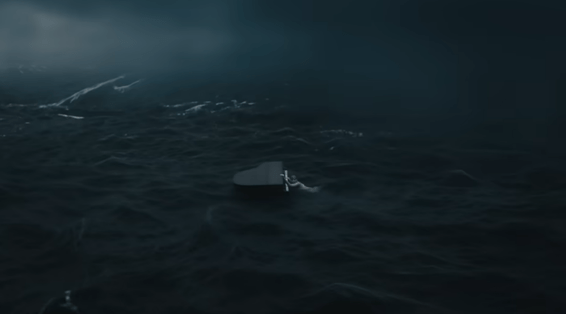

I’m on waves, out being tossed; is there a line that I could just go cross?

Taylor (as Vernon repeats his section in call-and-response):

And when I was shipwrecked, I thought of you.

In the cracks of light, I dreamed of you.

It was real enough to get me through.

But I swear, you were there.

I’ve already felt the cost of my cancer, the things lost: time, energy, professional opportunities, mental drain, the pain of side effects, the burden on my family. And much greater costs may lie ahead. I’ve longed for the kind of pause that Vernon describes, and have appreciated those times of rest when they have come. I’ve also felt shipwrecked, storm-tossed, and the imagery here calls to mind the lament of the psalmist in pain: “All your breakers and your waves have gone over me” (Psalm 42:7, ESV).

A foundational aspect of the lyrical anatomy of almost every Taylor Swift song is this: It is sung in first person, by an “I” (usually but not always Taylor Swift) singing to a “you.” There’s almost nothing in the way of a third-person story about a girl named Lucky, and when Taylor gets close to something like that, she still shows up to buy the Rhode Island mansion at the end of the song. Normally the “you” is easy to identify, at least generally, if not specifically. Often “you” shows up in the first verse.

Not in “Evermore.” “You” doesn’t show up until this bridge. And it’s never entirely clear who this “you” is, present in the cracks of light in the midst of a shipwreck storm.

I don’t know how much overlap there is between the Swiftie and Tolkien fan bases, but I’m in the center of that Venn diagram. I adore Tolkien, not only as a fantasy author, but as an academic who put his faith in conversation with his scholarship. During my cancer journey, I’ve thought not only of Taylor shipwrecked on the sea, but also of suffering Frodo, faithful Sam, and the grace of God that brought about the culminating victory at Mount Doom.

Tolkien wrote fantasy, and he theorized about it. As a communication theory textbook author, I approve. In his essay “On Fairy Stories,” he coined a memorable new word: “eucatastrophe.” In a letter to his son, he defined the term succinctly: “the sudden happy turn in a story which pierces you with a joy that brings tears.” The endings of Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, and The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe are good examples. In the Taylorverse, examples might include “Love Story” (with her dad’s unexpected change of heart) and “Long Live” (where the “band of thieves of ripped up jeans” unexpectedly gets to “rule the world”).

For Tolkien, the eucatastrophe is more than a literary device. It is a window into a deeper truth about the way the world works. Much of human life involves sorrow, pain, heartbreak, and death. We inhabit a world filled with conflict and war, cancer and disease, decay and loss.

It would be easy to conclude that this is the permanent, inevitable way of things. But Tolkien did not believe this. Nor do I. The eucatastrophe “denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and in so far is [gospel], giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.“

Here, in this season of Advent, Tolkien’s most famous quote about the eucatastrophe clarifies why he had such hope: “The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man’s history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. This story begins and ends in joy.“

“What does this have to do with ‘Evermore’??“, the patient Swiftie reading this may wonder. Well, further into Tolkien’s letter, I was struck by the parallel between his words and the lyrics of “Evermore:” “In the Primary Miracle (the Resurrection) . . . you have not only that sudden glimpse of the truth behind the apparent [nature] of our world, but a glimpse that is actually a ray of light through the very chinks of the universe about us.” That sounds a lot like cracks of light through the storm clouds on a shipwrecked sea.

Tolkien further describes riding his bicycle past an infirmary, when he “had one of those sudden clarities which sometimes come in dreams. . . . I remember saying aloud with absolute conviction: ‘But of course! Of course that’s how things really do work’. But I could not reproduce any argument that had led to this, though the sensation was the same as having been convinced by reason (if without reasoning).” Swift expresses a similar sentiment, more concisely and beautifully, in the closing verse of “Evermore”:

And I was catching my breath

Floors of a cabin creaking under my step

And I couldn’t be sure

I had a feeling so peculiar

This pain wouldn’t be for

Evermore

Let me be clear: I’m not saying that Taylor Swift wrote “Evermore” to express faith-based ideas. The popular theory is that the song is about her famously difficult year in 2016 and how Joe Alwyn (a.k.a. William Bowery, who has songwriter credit on “Evermore”) brought joy out of that season. It’s also a song released during the pandemic, and during that long season, I certainly longed for a pause to be certain we’d all be tall again.

Yet it is also a song that is a powerful, beautiful, and general artistic description of pain, grief, and loss. And in writing about such things, I cannot help but have the sense that the lyrics find their way to something deep and true for those who are in Christ.

If I may be permitted one more moment of listener interpretation that surely moves beyond what the writers of “Evermore” intended, I was struck by Vernon’s cry: “Is there a line that we could just go cross?” The lyric seems to express a desire for relief, for refuge, maybe even in death. Of course, “cross” here is used as a verb; but the word is also a noun. A particularly sacred noun. In my pain, in my fear, in my longing to not be a burden on my family, in my guilt about not paying attention to those very few signals that might have led me to get a colonoscopy sooner—in those moments most overwhelming, the cross of Jesus, an emblem of brutal death that has become an emblem of unending life, has been my only refuge, the only place I can go to find relief.

I long for my current story to be one that ends in eucatastrophe during my mortal life, to get scans that speak to a cancer thoroughly destroyed, whether as a miraculous answer to prayer or the Lord working through the power of modern medicine. That may not happen. But the cross and the empty tomb speak to a more-than-certain hope, a feeling so peculiar, an absolute conviction that, one day, the world will be made right and I will have a resurrected body, like that of Jesus, that is cured of cancer. It is a hope “beyond the walls of the world” available to all who put their faith and trust in Christ.

I cannot speak definitively to the authorial intent of “Evermore,” and I am not a postmodernist; I believe authorial intent matters. But in the corridors of my mind, the shipwreck is my cancer diagnosis; the waves are the challenges and suffering of treatment. And the cracks of light are the love and support of family and friends, in part. But that undimmable light, more real than even the reality of my suffering, is most supremely the gospel, the good news in which is all my hope: that Christ came as a baby, fully God and fully human, lived the perfect life I could not, died the death and took the wrath of God that I deserved, and three days later walked out of his own tomb.

And the mysterious “you” in “Evermore” is for me, then, Emmanuel, God with us: the Wonderful Counselor, the Mighty God, the Everlasting Father, the Prince of Peace. This December, as I sing Advent songs with tears in my eyes, this is my joy and hope, and why I am certain my pain won’t be for evermore.